Ethnic Differences and the Bible

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

(The first blog in this series can be found here.)

Controversies in America abound over race, culture, ethnicity, diversity and pluralism, nations and nationalism – the list is long and getting longer. How do we begin to sort through them as Christians?

As a starting place, one of the most helpful passages in the Bible is Acts 17:16-34. It records the apostle Paul’s visit to the city of Athens, one of the most important places in the ancient world. Many traditional conservatives still view Athens as a symbol of the philosophical power of Western Civilization.

Paul proceeds to shine the light of God’s truth into this dark city, which is filled with the idolatry of false religions. The apostle tells the Athenians that God “Himself gives to all people life and breath and all things” (vs. 25).

Most Christians are familiar with the first two gifts mentioned here by Paul – “life and breath.” We know from Genesis 1 that God formed Adam from the dust of the ground, breathed life into him, and created the first man in His own image.

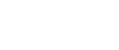

All men and women are descended from Adam, which means all people are related to each other. In this way, all human beings are considered “the children of God” (vs. 29). Of course, typically in the Bible, the concept of children of God refers to people who are in covenant with Him through the work of Jesus Christ (Rom. 8:14; Gal. 3:26; 2 Cor. 6:18.) But here Paul is using the phrase to link all people as members of one race, descended from Adam, who was created by God.

Distinctions fashioned by God

Despite the unity of the human race and our connection to one another, it is clear from this passage that God separated us into distinct nations. Paul says, “He made … every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth,” (vs. 26). God, Himself is responsible for this state of affairs.

The word “nation” is the Greek word ethnos, from which we get the English word “ethnicity.” Generally, the word ethnos refers to a distinct people who share a culture. While “culture” is itself sometimes a hard-to-define concept, it is commonly understood to mean the common language, law, customs, religious beliefs, etc. of a people who live together.

In the New Testament, variations of the word ethnos could sometimes be broad enough to include all non-Jewish peoples, as in Acts 18:6, “I will go to the Gentiles [ethne].” In other words, the Gentiles, who were all idolatrous peoples, were like one big pagan culture.

The fact that the English word used to translate ethnos is “nation” – at least in my NASB translation – is understandable. Common ethnic communities group themselves together, and if the group is large enough, in more modern parlance it is called a nation. But in New Testament times, not every ethnos had what we would understand as a nation. There were Thracians, for example, but no nation of Thrace per se.

We see this idea of ethnos displayed in Acts 17, as the Athenian philosophers, operating from a shared background, examine Paul’s ideas. Even though there were different philosophical factions in Athens – Epicureans and Stoics are named in vs. 18 – they were Greeks. Paul was seen as proclaiming “strange deities” and as “bringing some strange things to our ears” – meaning that all this was alien to the Athenian worldview.

One of the most interesting things about this passage is that there is nothing indicating that these ethnic and national differences are abhorrent to God. In fact, it appears that He has ordained these distinctions. Paul states flatly that God “determined their appointed times and the boundaries of their habitation” (vs. 26). He established the when, where, and how long of their existence.

All this is to say that the idea of ethnos is biblical. Distinct cultures, ethnicities, and nationalities not only existed, they were God-ordained. Therefore, as a simple fact of human existence, the ethnos was benign. It was morally neutral.

You ≠ Us

Let me demonstrate this fact more thoroughly. I mentioned Greeks in the city of Athens. However, the truth was that historically speaking, Greeks in Athens in many ways saw themselves as different from the Greeks of Sparta, Thessalonica, and elsewhere. There’s just no way to stop people from saying, “You aren’t one of us,” or, in a more Southern manner of speaking, “You ain’t from around here, are you?”

This was true about the Jews, too. Jesus was once told that some Greeks wanted to see Him (John 12:20). We know that the Jews stayed separate from Gentiles because the holiness code in the Law of Moses required it. These were Greeks, not Jews, who wanted to see Jesus, and this distinction could determine whether or not He would agree to meet with them. Moreover, the type of Greek isn’t mentioned. Were they from Athens? Corinth? It doesn’t appear to matter. Maybe the Jews thought, “Greeks are Greeks. What does it matter what specific city they’re from?”

Another example of this is the interaction between Jesus and the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4. In the discussion, there is a clear sense of “we” on the part of both Jesus, speaking on behalf of the Jews, and the woman, speaking on behalf of the Samaritans. Likewise, both understand that “we” are distinct from “you,” as when Jesus says, “You [i.e., the Samaritans] worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews” (vs. 22). There is no sense of illegitimacy here, that Jesus thought that cultures should not be different from each other. (As to what God thought about how the Samaritans worshiped, that is the subject of my next blog.)

It was normal and natural for people in the Bible to recognize these differences. In Ruth 4:1-5, for example, Boaz is discussing with the elders of the city about Naomi’s return from the land of Moab. When the discussion turns to Ruth, she is identified as “Ruth the Moabitess.”

Even a different accent was considered a distinction that could pigeonhole someone. Most of us are familiar with Peter’s attempt to distance himself from the just-arrested Jesus, although the attempt failed:

“A little later the bystanders came up and said to Peter, ‘Surely you too are one of them; for even the way you talk gives you away’” (Matthew 26:73).

When Paul rebukes the Christians in Galatia for thinking about retreating from the gospel, he criticizes them as a group: “You foolish Galatians” (Galatians 3:1).

That correction was based on a momentary, though potentially tragic, spiritual misstep. But sometimes an ethnos comes in for a much broader beat down. Take Paul’s comment about the people of Crete:

“One of themselves, a prophet of their own, said, ‘Cretans are always liars, evil beasts, lazy gluttons.’ This testimony is true” (Titus 1:12-13).

Well, that’s kind of harsh, but if we believe Paul was inspired by the Holy Spirit to write this, then apparently God believed it was true, too.

(Notice that while it was not “wrong” to be a Cretan – as opposed to being a Greek or a Scythian or a Roman – the morality of the Cretans is what comes in for harsh criticism. This is a hint about what we will discover in future blogs.)

This is as good a place as any to stop. My first conclusion is this:

The Bible speaks of differences between us, and in terms of ethnos, God created some of these distinctions. Those differences that are created by God are benign, akin to hair or skin color.

That leaves many questions unanswered, among them: What is the purpose of these differences? Should we accept distinctions and maintain them, seek to create new, multicultural expressions of our humanity, or some combination? Do differences give us the right to mistreat those who are outside our group? What does the coming of the gospel mean for these distinctions?

These are questions I hope to answer in the weeks ahead.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.