Overpaid Hypocrites Still Lecturing Us

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

Unsurprising to most, and to the chagrin of many, the NFL kicked off their season this past weekend by disrespecting our flag, anthem, nation, and soldiers.

The theatrics on display were varied. Most teams, for the sake of raising awareness, engaged in some form of protest against alleged injustice and inequality.

Messages in end zones, names on helmets, raised fists, kneeling or sitting during the anthem, and even a separate black anthem were all on-field antics fans who simply wanted to watch some football were subjected to.

Partiality, privilege, injustice, and inequality certainly exist, just not in the context it’s being suggested today. It reaches across ethnic boundaries and can and does affect everyone.

The absurdity of it all

When the protests began with Colin Kaepernick in 2016, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said he didn’t “necessarily agree” with what Kaepernick was doing. He’s recently had a change of heart, however, stating in early June,

“We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all to speak out and peacefully protest. We, the National Football League, believe Black Lives Matter. I personally protest with you and want to be part of the much-needed change in this country.”

Goodell continued,

“Without black players, there would be no National Football League. And the protests around the country are emblematic of the centuries of silence, inequality and oppression of black players, coaches, fans and staff. We are listening. I am listening…”

I’m trying to understand, but I’m confused.

Goodell said the NFL wouldn’t exist without blacks. Isn’t the point in all this to fight racism? Maybe racism only goes one way, but it sounds racist to me to insinuate that whites are no good at football. Don’t get me wrong, in no way am I a proponent for an all-white league. These black men are amazing athletes and contribute so much to the game, but Goodell’s statement is racist.

Goodell said the protests are emblematic of the “oppression of black players.” Wait a second. I thought he said the NFL’s existence was predicated on blacks. If an entire organization’s existence depends on one demographic, how is that demographic oppressed?

He also mentioned the “inequality” of black players. Let me speak to inequality. In the NFL, which is 70% black, the average annual salary is $2.7 million. According to spotrac.com, the top three league earners for 2020 are Patrick Mahomes at $45 million, Deshaun Watson at $39 million, and Russell Wilson at $35 million. The top three earners are black by the way.

Now compare that to the average annual salary of teachers, clergy, law enforcement, military, medical professionals, and workers in other vital fields – most of whom make less than $50,000 per year

Those in the league are “privileged” to make millions per year playing a child’s game for a living, while those who make truly invaluable contributions to society are usually just happy to pay their bills.

Don’t misunderstand. I’m not against their exorbitant salaries. Capitalism at work is a beautiful thing. I just find it disingenuous for the few, with their privileged, indulgent lifestyles, to lecture us on how to overcome disparities.

A veteran’s perspective

My grandfather served in the Army as a cryptographer for the Signal Corps in Japan during the Korean War. Because he spent his time there in relative safety intercepting, coding, and decoding top-secret messages, he often said he never considered himself a hero. He always said the guys who stormed the beaches of Normandy, those who fought on the island of Iwo Jima, and other soldiers on the front lines were the real heroes.

I disagree with his assessment of what constitutes heroism, though I must admit I share the same sentiment when it comes to my military service.

I followed in his footsteps and joined the Army and just a few days after graduating high school I was off to basic training.

In 2003, at just 20 years old I found myself in the scorching desert sands of Iraq. Many people have childhood dreams of serving in the military – I didn’t. In fact, as a child I can remember my parents watching movies about the military and war, and quite frankly, the thought of it all scared me to death.

I matured, however, and as the typical calls from recruiters began coming in my senior year of high school, I found myself entertaining the idea of serving. They convinced me and on April 26, 2000, I was sworn in.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks on 9/11, I had a strong feeling we’d soon be at war. My intuition was correct, and in less than two years, I found myself living amongst, and fighting against the very ones who had recently attacked and changed our nation and way of life.

In many respects, war was just as I’d imagined it would be as a child. In many ways, however, in ways I’d never considered, it was actually worse. In some ways though, strangely enough, it wasn’t as bad. I know that dichotomy doesn’t make sense, and I can’t really explain it, but that’s just the way it was.

I spent nearly a year in Iraq’s Sunni Triangle, considered at that time to be the most dangerous place in Iraq. While there my fellow soldiers and I became familiar with the peculiarities of war. Weeks without baths, rationing food and water, and no contact for weeks on end with family were some of the earliest adjustments we had to make.

We learned quickly that our enemy was difficult to fight. Their modus operandi was to attack and then disappear like the cowards they are.

Mortars raining in on us, taking on small arms fire, and hearing bullets and watching incoming tracers light up the night sky became a common scenario. I don’t think I’ll ever forget the welcomed sound of the 155 mm howitzers firing off in response to our ghostlike enemy’s attack and hide tactics.

Our duties were various and many. Sometimes we destroyed, sometimes we built. But whether we were fortifying a base or clearing the roadside of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), our goal was to serve our country with pride.

I’m not sharing this in any way to be self-aggrandizing. Like my grandfather, I certainly don’t consider myself to be a hero. In fact, I very rarely mention my service, not because I’m ashamed of it though. I consider it an honor and am proud to have served. But when I consider what little I faced, compared to what the heroes before me endured, it seems a bit flippant to put myself in a group with them.

Those before us

I sincerely believe that if those who claim to have no problem with the disrespect would only put themselves in the shoes of the soldiers of previous generations who gave so much, they would see things differently.

Consider D-Day, when at least 150,000 Allied troops stormed the beaches of Normandy in an effort to drive the Nazis out of Western Europe and turn the tide of WWII. Over 4,400 men lost their lives in less than 24 hours, over 2,500 of those being Americans – 2,000 of whom were killed on Omaha beach alone.

Over the next two months, up until France was liberated, nearly 73,000 more Allied service members were killed or missing, and more than 153,000 were wounded. In total, WWII cost this nation over 405,000 American soldiers. My grandfather always said if it weren’t for their grit, determination, and sacrifice, “We’d all be speaking Japanese today.”

You’ve likely never heard of the Meuse-Argonne campaign of WWI, the largest offensive in U.S. military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. The objective of the Allies was to capture a railway hub that would break up the German Army’s support network.

They were successful and the battle ultimately brought an end to WWI, but not without a cost. It was not only the largest offensive but also the deadliest in American history, costing 26,277 soldiers their lives in less than 50 days.

There are countless more battles I could list, but in total over our brief 244-year history as a nation, more than 1.1 million Americans have given their lives in service of this great country.

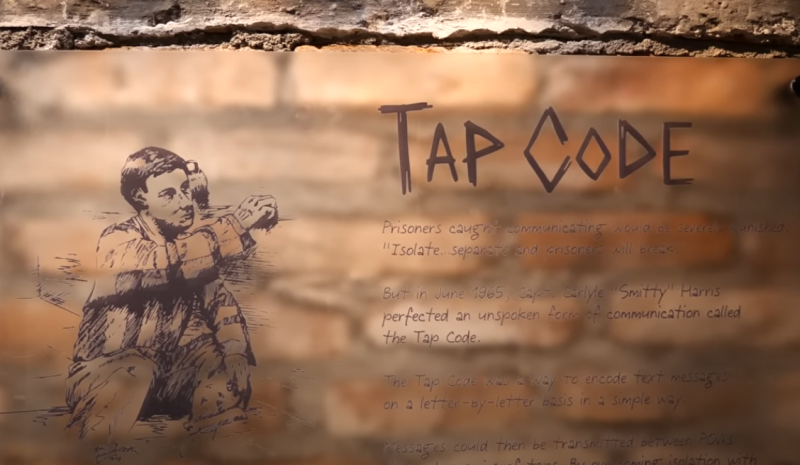

Aside from those who made the ultimate sacrifice, over 140,000 spent time as prisoners of war, and nearly 82,000 soldiers dating back to WWII until the present are still missing today.

In all American conflicts combined, in addition to those KIA, POW, and MIA, over 1.4 million soldiers have been wounded, many who lost limbs and were/are severely disabled.

Hundreds of thousands of veterans currently suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and an estimated 20 veterans per day are committing suicide.

The very freedoms we enjoy today are the direct result of millions of men and women who have proudly worn the uniform, served, and sacrificed greatly.

They loved the flag

Countless are the stories of soldiers who’ve both lost and risked their lives to advance the very flag under which they were fighting. One such story is that of Army Sgt. William H. Carney.

When the Civil War broke out, Carney, who originally hoped to serve in ministry, decided the best way he could serve God was by fighting to help free the oppressed. He became an infantryman in the Union Army.

On July 18, 1863, as Carney’s regiment led the charge on Fort Wagner in Charleston, South Carolina, their unit’s flag bearer was fatally shot. Carney, only a few feet away, saw him falling and determined not the let the flag hit the ground, caught it, and raised it high.

In his efforts to continue the advance, Carney was shot twice in the leg, in his chest, his right arm, and grazed in the head. When the battle ended, he said to his fellow soldiers, “Boys…the flag never touched the ground.”

His heroic actions served as an inspiration to the other soldiers and was crucial to the North securing victory at Fort Wagner. By the way, Carney was black. Obviously, the flag meant something to him, regardless of his skin color.

Because of his bravery, Carney was awarded the military’s highest award, the Medal of Honor, becoming the first black man to ever receive it. He knew the significance of the flag flying high.

The flag gave hope

In fact, in a battle nearly 50 years earlier, it was the fact that the “flag was still there,” that inspired Francis Scott Key to pen the poem that we know today as the Star-Spangled Banner, our national anthem.

During the War of 1812, after British troops had invaded Washington, D.C., and set fire to the White House, they set their sights on overtaking the key seaport of Baltimore, Maryland. Specifically, they planned to take Baltimore’s, Fort McHenry.

Key was aboard a British warship some eight miles out in the Baltimore harbor negotiating for the release of a local American doctor who’d been captured in an earlier battle. Though they agreed to release the doctor, they would not allow Key to leave for fear that he would quickly make way to land and inform the American soldiers of the impending attack.

As a result, Key watched for some 25 hours as Fort McHenry endured non-stop pounding by the Royal Navy. He knew that as long as the flag still waved though, America was holding her own. As darkness fell, however, the only indication he had that freedom was surviving was “the rocket’s red glare,” and “the bombs bursting in air,” as their explosions lit up the darkened sky just enough to give “proof through the night that our flag was still there.” Glimpses of that flag gave hope that freedom endured.

When morning broke and silence fell, Key realized the shelling hadn’t stopped because America had surrendered. The shelling stopped because the sight of the American flag still waving in the morning light broke the will of the British commanders, and they realized they couldn’t win. This was a crucial victory in what some consider America’s second war for independence.

What the flag means today

Of the nearly 200 countries in the world, how many national flags could you recognize? If you’re like most people here in America it would likely only be a few.

But consider that almost every other nation around the world recognizes ours. Why? Because it symbolizes a country that grew weary of oppression and fought a bloody battle to secure its freedom. What it represents is the envy of people around the world.

In a radio address to the nation President Reagan once said, “With the birth of our nation, the cause of human freedom has become forever tied to that flag and its survival.”

Reagan went on to say, “Let us never forget that in honoring our flag, we honor the American men and women who have courageously fought and died for it over the last 200 years —patriots who set an ideal above consideration of self and who suffered for it the greatest hardships. Our flag is free today because of their sacrifice.”

It’s not about the flag?

The protestors say it’s not about the flag or the country. In June, Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers posted on Instagram, “It has NEVER been about an anthem or flag. Not then. Not now.” Houston Texans J.J. Watt echoed Rodger's comments later in June, posting to Twitter, “…If you still think it’s about disrespecting the flag or our military, you clearly haven’t been listening.”

I think people have been listening, and apparently, they don’t like what their hearing. Football enthusiast and reporter for The Daily Caller, David Hookstead, tweeted on September 14, “The NFL’s TV ratings have cratered, and are reportedly down 28% to open the season compared to 2019. This is what happens when you make sports about politics. People stop watching.”

Sounds like a simple fix to me. If it’s really not about the flag, find another way to protest. Maybe they could put their money where their mouth is and start funneling their millions into programs to help those who are “oppressed.”

Their right

Many defend the actions of the protestors, saying it’s their right, citing the 1st Amendment. I couldn’t agree more.

A unique relationship exists between those who abuse their rights and those who serve to protect them. American’s rights are so valuable, that even when they are abused to the disrespect of the very one who fought to sustain them, they’ll still support that right, and if needed, fight and die for it.

Do they have the freedom to disrespect the flag and our nation? Yes, they do. Do you have the freedom to support them? Absolutely.

But as they kneel or refuse to place their hand over their heart, just remember that somewhere there’s a veteran who lost his legs fighting for that right. He’d love to stand. Somewhere there’s a veteran who lost an arm fighting for that right. He’d love to salute.

I’m proud you and I have that freedom, but please, remember where it came from, and exercise it wisely.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.